Article: Art 101 | Femme Surrealism: Reclaiming the Dreamworld

Art 101 | Femme Surrealism: Reclaiming the Dreamworld

Surrealism has long been associated with dreamlike visions, subconscious desires, and strange, otherworldly imagery. But for many women artists, it was more than just a movement—it was a means of reclaiming their own narratives. Femme Surrealism is a term that encompasses the work of female-identifying artists who have used Surrealist techniques and ideas to explore identity, autonomy, and the subconscious. From the early 20th century to today, these artists have pushed beyond the objectified “muse” to create their own surreal dreamworlds.

While the Surrealist movement, led by figures like André Breton and Salvador Dalí, often placed women in passive or symbolic roles, many female artists took Surrealist principles and turned them inward. Instead of serving as inspiration for male painters, they became the creators of their own visions—blending personal mythology, fantasy, and deep psychological exploration into their work.

Characteristics of Surrealism

Psychological Depth & Intuition

Surrealists lean into the subconscious, embracing dreams, emotions, and intuition as core elements of their creative process—an approach that aligns with Surrealism as a whole rather than diverging from it. Their work can encompass both Surrealist explorations of historically feminine themes—such as domestic ritual, motherhood, and the natural world—as well as Surrealist works created by individuals identifying as female, regardless of subject matter. In both cases, their contributions expand and challenge the boundaries of the movement, bringing new perspectives to its fundamental pursuit of the irrational, the uncanny, and the unconscious.

Autobiographical & Feminist Themes

Their work often explores self-identity, sexuality, motherhood, and personal trauma—offering a counterpoint to the traditional male gaze of Surrealism. It frequently refocuses attention onto unexplored states of physical or psychological interiors, domestic spaces, and traditionally female roles of caregiving and domestic labor, giving these themes thoughtful attention and sometimes even transforming them into realms of mystery, power, and self-invention.

Symbolism & Metamorphosis

Many Surrealists depict hybrid forms, fluid transformations, and dreamlike landscapes that blur the boundaries between human, animal, and nature. They often play with traditionally feminine symbols, either amplifying their meanings or subverting and questioning their assumed significance, reshaping them into tools of personal and collective mythmaking.

Mysticism & Nature

Themes of magic, astrology, folklore, and spiritualism frequently appear, reflecting a deep connection to both the metaphysical and the organic world. These works often blur the boundaries between the seen and unseen, grounding the mystical within tactile, lived experience. Symbols drawn from ancient traditions, celestial patterns, or esoteric practices are not merely decorative, but act as portals—ways of accessing knowledge beyond the rational or empirical. Nature itself becomes animate: forests hum with hidden consciousness, animals serve as guides or omens, and the cosmos is rendered not as distant abstraction but as a field of intuitive, embodied resonance. In this context, the mystical is not escapist—it is a method of perceiving the world more fully, attuned to forces that resist simplification.

Notable Femme Surrealists and Women Who Influenced the Movement

Frida Kahlo

Though Frida Kahlo famously rejected the Surrealist label—declaring, “I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality”—her work influenced the movement’s visual and psychological language. Her self-portraits are portals into the intimate, the wounded, and the visionary. Rather than escaping reality through fantasy, Kahlo unearthed the surreal within the everyday, turning her physical pain, emotional entanglements, and cultural identity into a theater of rich symbolic complexity. In paintings like The Two Fridas (1939) and The Broken Column (1944), she splits herself across dual selves, fractured spines, and open hearts, creating images that are both deeply personal and universally mythic. Her use of vivid symbolism—monkeys, bleeding hearts, thorn necklaces, desert landscapes—transcends autobiography and becomes archetypal, tapping into a broader feminine subconscious.

Kahlo’s art also navigates a profound political and philosophical terrain. She infused her imagery with questions of identity, nationalism, and gender, long before these became central to contemporary discourse. Her representation of the body—nude, injured, yet defiantly present—reclaims agency through vulnerability. In contrast to the objectified muses of traditional Surrealism, Kahlo’s gaze is unflinching, returned, and sovereign. Her paintings do not ask to be interpreted so much as witnessed—each a self-contained cosmos where pain, beauty, and resistance coalesce.

Though her relationship with Surrealism remained complex, Frida Kahlo’s legacy is inseparable from its evolution. Her radical introspection and symbolic storytelling cracked open the boundaries of the genre, carving out a space for personal mythology and feminine power that continues to shape the language of contemporary surrealism.

Leonora Carrington

Leonora Carrington’s work stands as an enigmatic portal into a realm where the boundaries of dream, myth, and reality become fluid. Renowned for her mystical, dreamlike paintings, Carrington’s art is a vivid exploration of the subconscious, where alchemical symbols and fantastical creatures reign. Her compositions, such as The Lovers (1949), immerse viewers in a world of transformation, where human and animal forms blend in a symbolic dance that defies rational logic. Her work transcends traditional representation, blending elements of surrealism with personal mythologies that are deeply connected to her own explorations of the occult and esoteric knowledge. Drawing from Celtic folklore, tarot, alchemy, and her experiences with spiritualism, Carrington constructs intricate narratives that challenge patriarchal structures and offer alternative cosmologies. Her paintings are not merely visual; they are spells, encoded with symbols of feminine power, metamorphosis, and resistance. Through her richly layered imagery, Carrington carved a space within the surrealist tradition that was uniquely her own—one where the inner world is sovereign, and imagination becomes a form of liberation.

Through the transformation of the female body into surreal, dreamlike forms, she challenges established narratives, positioning her figures as both vulnerable and empowered. Her symbolic use of animals, ritual, and metamorphosis speaks to a deeper understanding of self and other, where the viewer is invited to confront the mysteries of inner and outer worlds. In Carrington’s surreal landscapes, the rules of time and space are bent, creating a space where transformation is the only constant, and the language of the subconscious takes center stage.

Remedios Varo

Remedios Varo’s paintings are metaphysical blueprints—precise, hauntingly beautiful, and wholly otherworldly. A master of intricate, surreal compositions, Varo fused the arcane with the scientific, creating dreamlike narratives that dissolve the boundaries between reality and the subconscious. In works like The Creation of the Birds (1957), she imagines a woman, part scientist, part sorceress, conjuring life through an alchemical instrument—a violin-like device. Here, the act of creation becomes both a mystical and intellectual endeavor, where magic and science intertwine as one.

Varo’s approach to the female figure was unlike the passive muses often seen in Surrealism. Her women were autonomous, intellectual beings—scientists, philosophers, and alchemists engaged in esoteric quests for knowledge. In Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst (1960), she subtly mocks Freudian paradigms, depicting a woman literally extracting a tangle of roots from her chest—an act of self-liberation from the confines of psychoanalysis. Varo’s women are not mere dream figures but creators in their own right, deeply connected to the hidden forces of the universe.

Her paintings invite us into strange, ethereal laboratories and cosmic chambers where time bends, and the laws of nature are suspended. With exquisite attention to detail and an unmistakable blend of magic and logic, Varo’s work offers a vision of a world where intellect and intuition, reason and mysticism, coexist in delicate, luminous harmony.

Dorothea Tanning

Dorothea Tanning’s work exists at the threshold of reality and reverie, where the familiar distorts into the uncanny, and the human form is reshaped by the subconscious. Her paintings and sculptures, suffused with psychological intensity, center the female body in states of transformation—stretched, unfurling, dissolving—suggesting a struggle between containment and release.

Her early paintings, such as Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943), depict dreamlike interiors where figures, particularly young women, seem caught in a moment of metamorphosis. These spaces, rendered with meticulous realism yet imbued with an otherworldly charge, reveal her engagement with the Surrealist tradition. Fabrics ripple unnaturally, hair billows like flame, and doorways hint at passage into an unknown beyond. In Birthday (1942), Tanning positions herself in an enigmatic self-portrait, standing in an ornate jacket before an endless hallway of doors—a meditation on identity, autonomy, and the labyrinthine nature of self-discovery.

Her sculptural works, particularly those from the 1960s and beyond, take this fluidity further, moving from two-dimensional illusion to tangible form. In pieces like Rainy Day Canapé (1970), fabric-wrapped limbs push out from a settee, as if the furniture itself is absorbing or birthing the body. The forms are organic yet unsettling, a collision of softness and restraint, reinforcing themes of desire, confinement, and the blurred boundary between subject and environment.

Contemporary Artists working in Surrealism

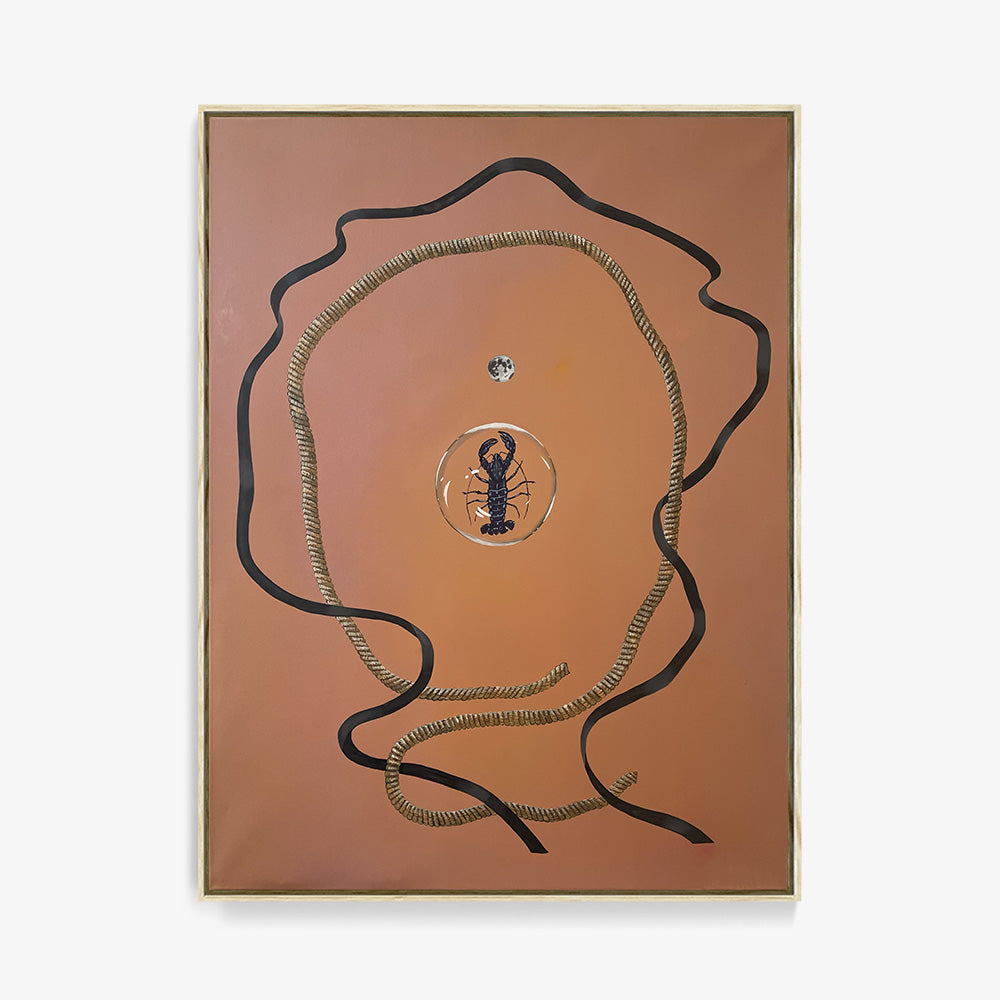

Brianna Lance

Brianna Lance’s surrealist dreamscapes unfold in a universe where the feminine is both mythic and mutable. She leans into an iconography long associated with femininity—shells, roses, orchids, lipsticks, horses—only to subvert and expand it, layering in unexpected symbols like braids, candles, and strands of hair. These objects, often hovering in ambiguous space or drifting toward one another with uncanny purpose, refuse to settle into mere decoration. Instead, they act as charged totems, hinting at hidden narratives, private rituals, and the ever-shifting boundaries of identity. In Lance’s world, femininity is not a fixed construct but a surreal force, flickering between desire, power, and the unknown.

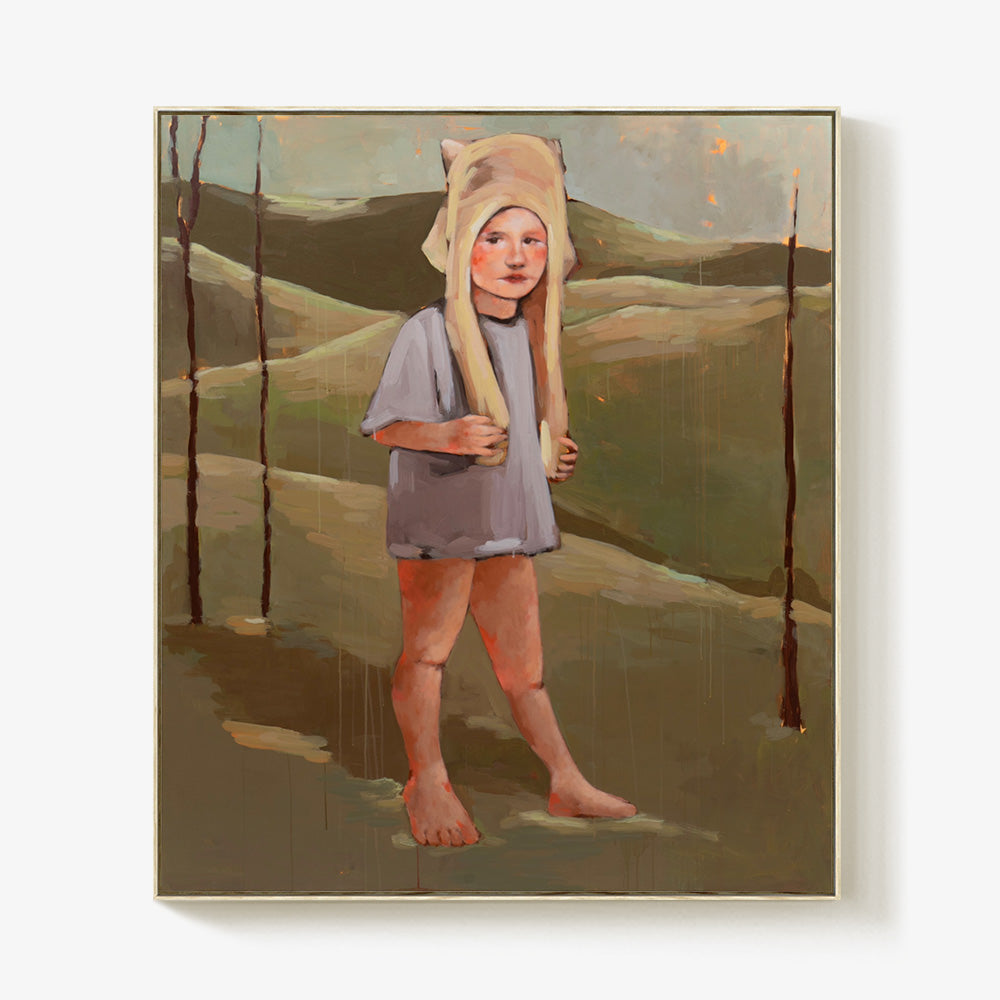

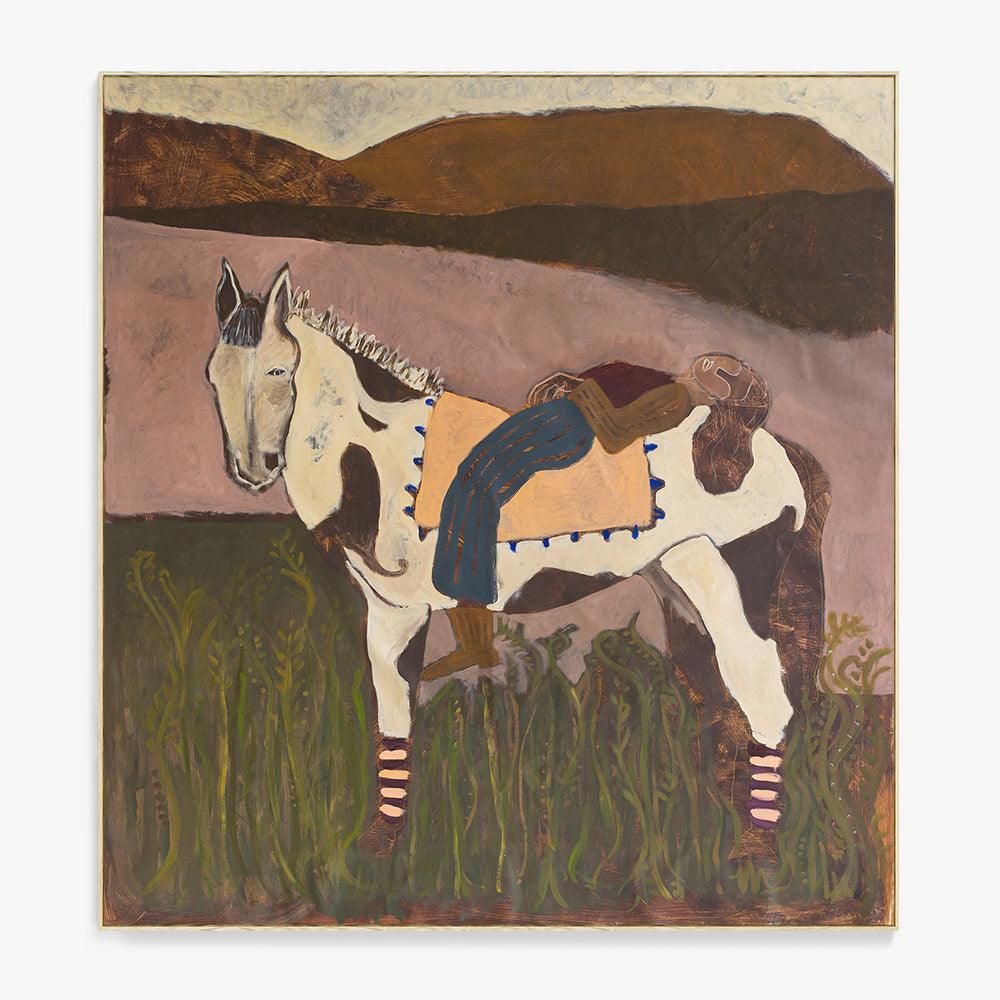

Kate Florence

Kate Florence’s imagined Western vignettes slip seamlessly into the surrealist tradition, where the everyday becomes uncanny and the familiar tilts toward the dreamlike. Like the surrealists before her, Florence reconfigures reality—not by abandoning it, but by amplifying its strangeness. Figures drift through indeterminate space, their gestures fluid and unresolved, while common objects take on an almost psychic charge. The Western iconography she draws from is less a setting than a fragmented dreamscape, where symbols shift and dissolve, resisting fixed meaning. In Florence’s world, intimacy and solitude exist in the same breath, and the ordinary is always on the verge of transformation.

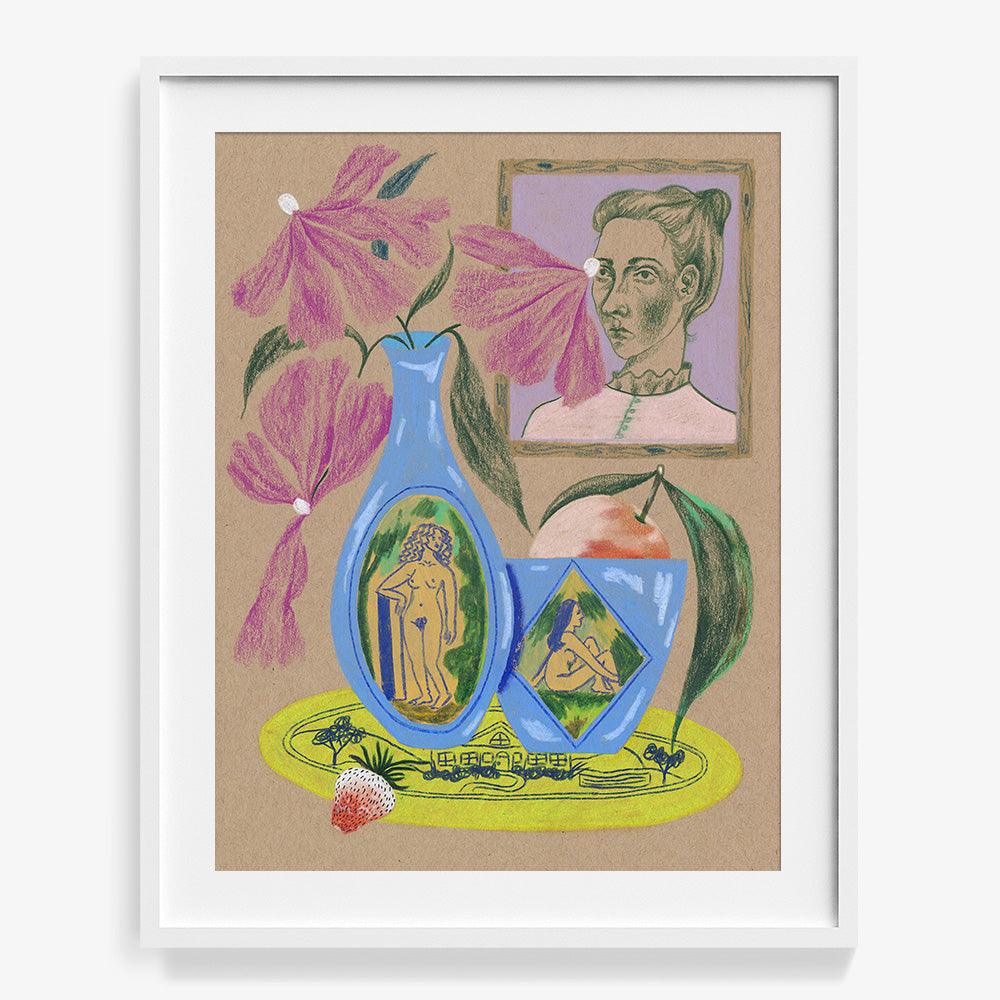

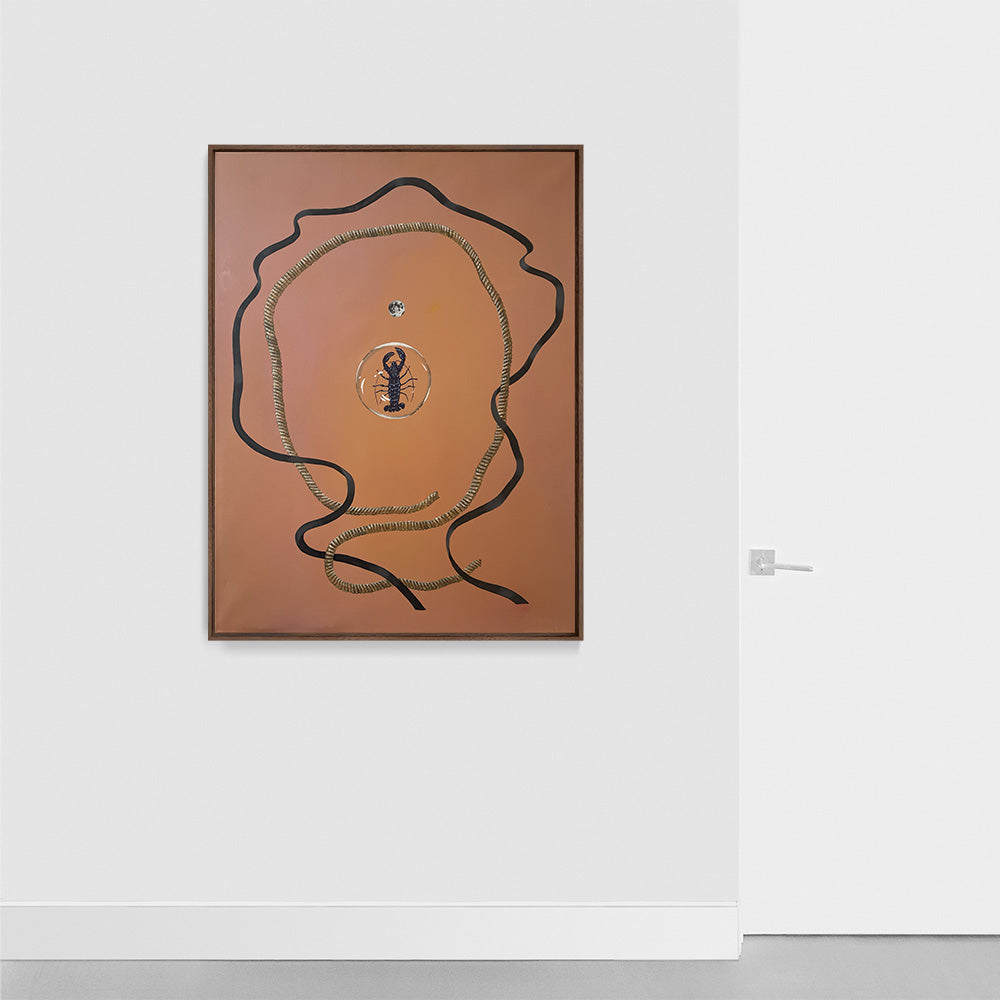

Laura Burke

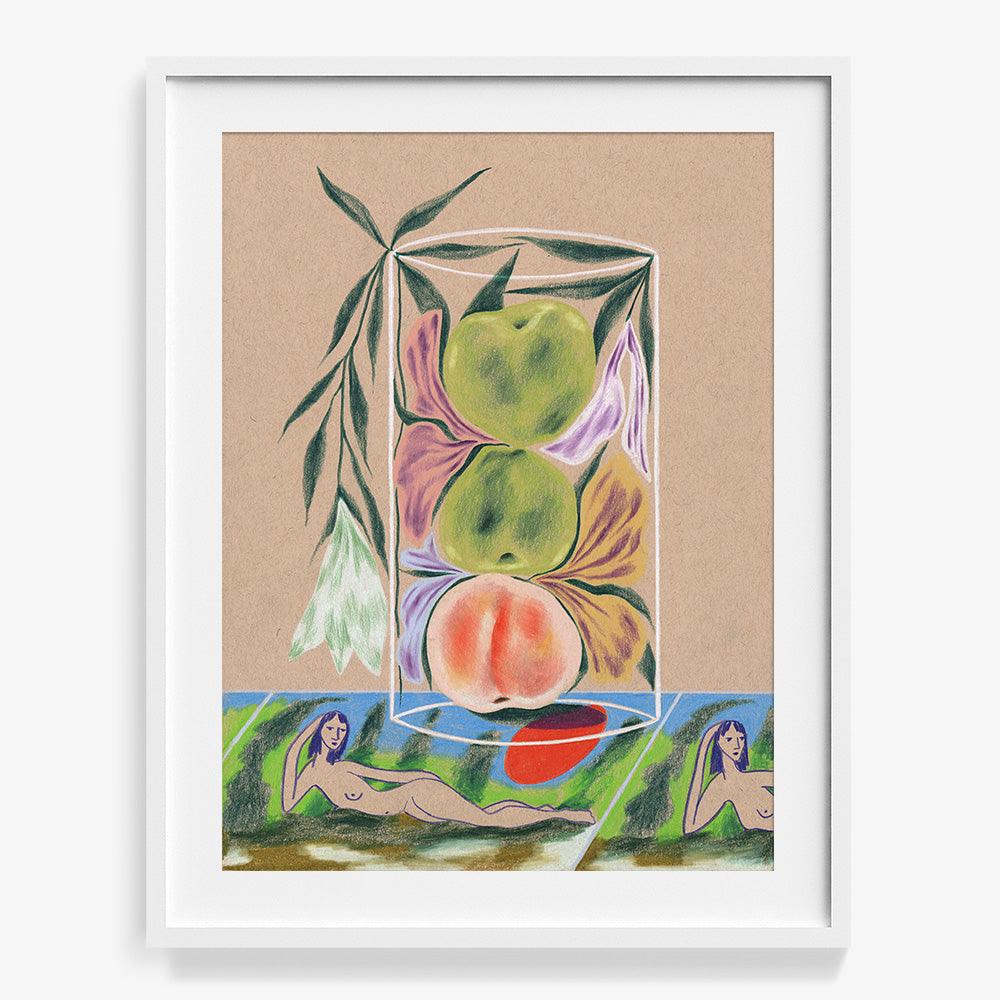

Laura Burke constructs still-life interiors where figures and familiar objects become anchors in surreal, dreamlike spaces. Blurring the line between the everyday and the uncanny, her compositions reimagine domestic scenes as portals into layered, atmospheric worlds. Through a surrealist lens, Burke transforms common interiors into realms of quiet tension and possibility, where the ordinary bends toward the extraordinary, and each object carries the weight of both memory and imagination.

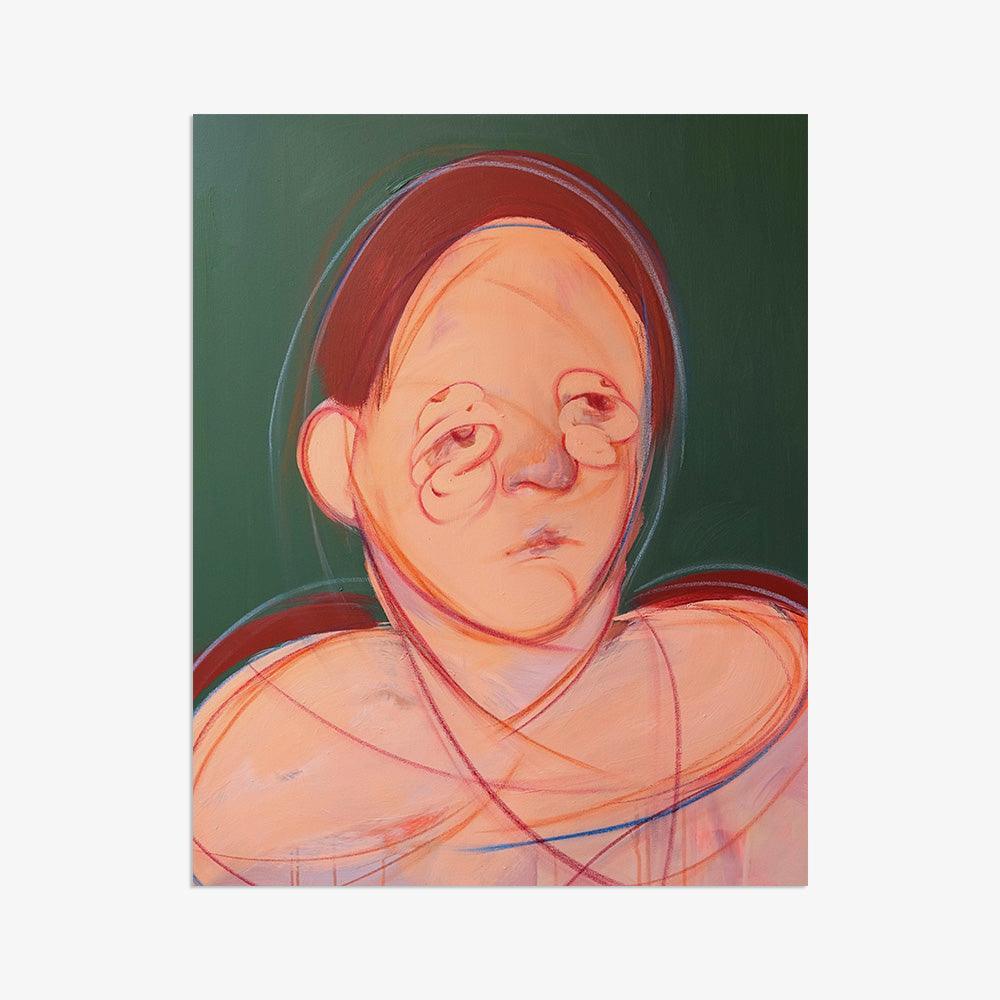

Irinka Talakhadze

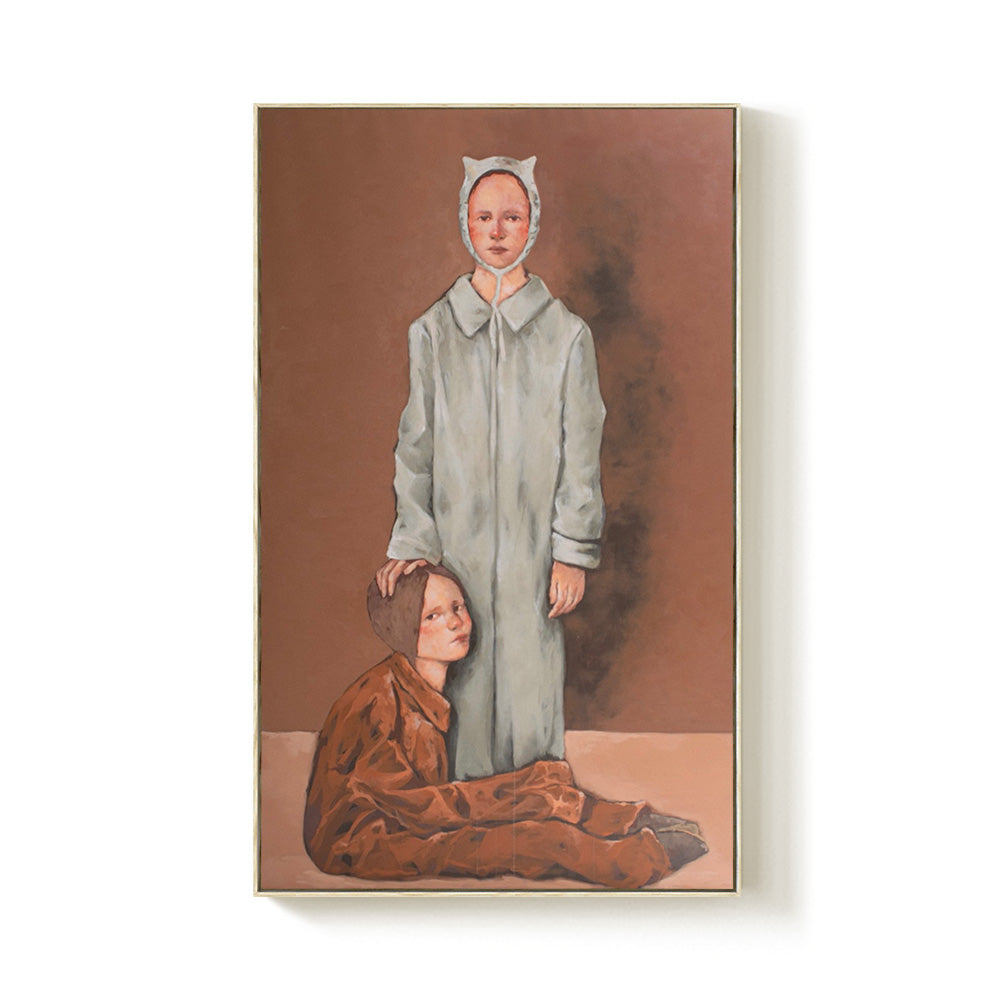

Irinka Talakhadze’s figures inhabit a world just off-kilter from our own—recognizably human yet subtly unreal, as if seen through a shifting lens. A slight elongation of a limb, a shadow bending the wrong way, or a gaze that lingers a moment too long unsettles the scene, hinting at the thin membrane between utopia and dystopia. Her work lingers in this liminal space, where an ideal can fracture under its own weight, where harmony teeters on the edge of collapse. It is a question of balance—whether imposed or lost—and of perspective, suggesting that paradise and ruin are often distinguished only by the eye that beholds them.

See more of Talakhadze’s work.

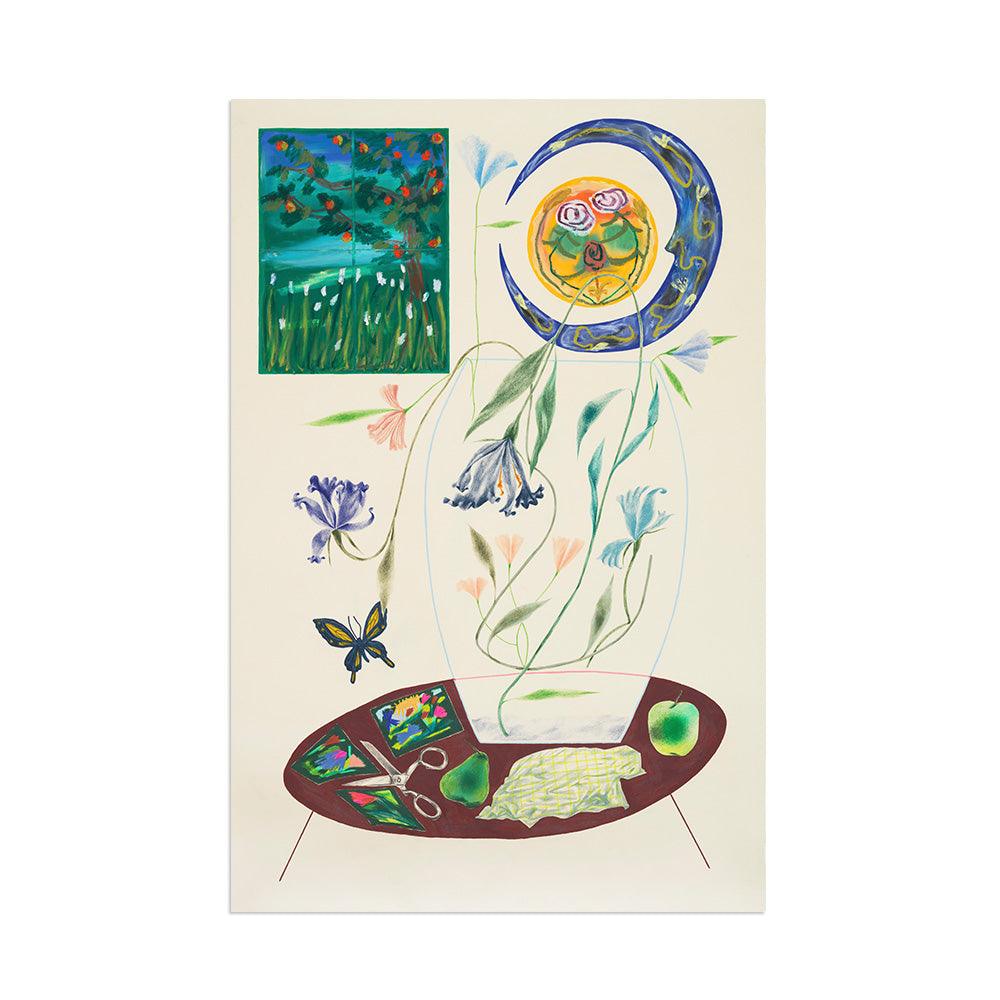

Virginie Hucher

Virginie Hucher’s work engages with Surrealism through restraint, rendering figuration not as spectacle but as meditation. Her paintings depict female figures in moments of suspended quiet—neither fully passive nor overtly assertive, but held in a kind of psychological tension. Birds, flowers, and references to classical statuary populate her compositions, yet they never feel ornamental. Instead, these motifs serve as entry points into a deeper exploration of what it means to embody both fragility and power. In Hucher’s world, softness is not weakness, but weight; beauty is not surface, but structure. Her figures—serene, unguarded, and composed—suggest a surrealism that is less about rupture than it is about refinement, offering stillness as a kind of radical interiority. Through this quiet surrealism, she reframes vulnerability as its own kind of force.